Lon Chaney

Jr was cast again by Hal Roach in the prehistoric dinosaur actioner One Million Years BC (1940) as Akhoba,

the Rock Tribe’s caveman father to Victor Mature. Amongst the Oscar-nominated

special effects, this film is notable for Chaney’s attempt to craft his own

make-up in respectful imitation of his father, stymied however by understandable

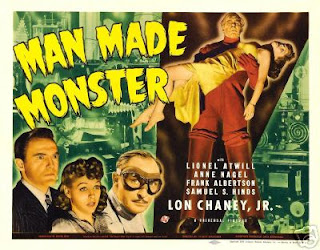

union regulations. Universal soon had him under contract and his first horror

film in his new flush of fame was the lead in the surprisingly effective

quickie Man Made Monster (1941). Five

years previously Harry Essex’s script almost became another of the Karloff and

Lugosi team-ups under the title The

Electric Man with the pair playing the victim Dan McCormack and mad

scientist Dr Rigas respectively. The plot’s marauding, luminous protagonist was

felt too reminiscent to their double-act in 1936’s The Invisible Ray (see my review dated 21/7/2016) and was shelved

till Universal’s new regime recycled it.

Shot in only

three weeks, Man Made Monster was

indicative of Universal putting little weight of expectation behind it at a relatively

very low budget of just $86,000. They couldn’t have known that under director

George Waggner it would emerge is a credible introduction to Chaney in the

genre. His character of Dan McCormack echoes the eager-to-please guilelessness

of Lennie in Of Mice and Men as

carnival performer Dynamo Dan, the Electric Man whose phoney act hints at his

destiny when he is the sole survivor of a bus crash that crashes into a live

electric pylon.

By sheer and

contrived coincidence, Dan is befriended by Dr John Lawrence, (another kind,

dignified authority portrayal by It’s a Wonderful

Life’s Samuel S. Hinds) who just happens to have an associate obsessed with

that very source of power: Lionel Atwill’s Dr Paul Rigas. Atwill does his best

to represent maniacal self-serving menace in contrast to Lawrence’s benevolence

in having Dan live with his family while under observation. By now Atwill was

enjoying a run of Universal horrors that began with 1939’s Son of Frankenstein (reviewed here) through till the year before

his death in House of Dracula (1945).

He would be gratefule for the work as during this period in 1943 he suffered

the five-year probation sentence (see 21/4/2016) that blacklisted his

reputation into a humiliating dearth of good roles.

Knowing his own

star in the ascendant, Chaney is given much more to work with and seizes the

role of Dan with compassion and presence. His energy on-screen is boosted by

Rigas secretly blasting him with electricity while Lawrence is away at a

convention. The melgalomaniac believes he can create a race of ‘electralised’ souped-up

supermen, invulnerable to weakness – “whose only want is electricity” - and Dan’s

odd survival makes him the perfect guinea-pig. Over time, the electrical jolts

turn from tolerance to a ruinous addiction in Dan who gradually becomes a

listless walking shell of his former self, fatally dependent upon increasing daily

doses to feel anything at all. Chaney earns our sympathy with his gradual decline

from sunny innocence to a haunted and damaged victim. Make-up wizard Jack

Pierce augments this deterioration with etched lines of aging to Chaney’s face

through which he emotes his heartfelt confusion. His alienation is amplified by

a reverse Midas effect that causes crackling bolts of electricity to sear

anything he might touch. No wonder his canine pal, Lawrence’s dog Corky, keeps

his distance.

Such is

Rigas’s merciless drive that finally he shocks Dan to laboratory capacity, erasing

Dan’s former lightness of soul into a luridly glowing, lumbering servile

automaton encased in an insulating rubber suit. John P Fulton of Invisible Man effects fame provides a

suitable luminescence for Dan’s face and arms while Rigas sheds further light

on his own inner machinations to Lawrence: “Look at him. The wonder of the

future – controlled by a superior intelligence!” No prizes for guessing who the

latter is. Rigas orders Dan the battery-powered battering ram to kill Lawrence

by breaking his neck. He is powerless to refuse.

The aftermath

is that Lawrence’s daughter June (Anne Nagel) appeals to William Davidson’s

slightly wooden District Attorney Stanley for Dan’s innocence to no avail. As

if he hasn’t been charged enough, the ensuing court case results in Dan

sentenced to an electric chair of all things and a phosphorescent rampage that

would have been welcome if it wasn’t off-screen to save money.

No matter,

there’s still some juice left firstly to power Atwill in a finely chilling scene

with Nagel, looming over her with a sickeningly perverse grin of anticipation

before strapping her to the operating table. He intends to take his sadism to the

even higher voltage of preying on a suspected more potent female subject.

Suddenly Dan enters to save the day. Like Frankenstein’s lightning-induced

offspring, he channels his rage against his quasi-creator, electrocuting him

through a door-knob before carrying June away.

The police manhunt

is now on for Dan the marauding lightbulb. June’s boyfriend, newshound Mark

Adams (Frank Albertson, who later played Tom Cassidy in Psycho) accompanies them with the D.A. and even Corky the dog in

hot pursuit. The ultimate tragic end for our hapless hero comes courtesy of a

ripping time for his suit, snagged on an electrified fence, which may sound

prosaic, yet Chaney senior would have been proud of his son’s movie demise. There is an affecting physicality to the slow

buckling of his legs under the terminal energy leakage; an otherwise rushed

moment is given poignant weight, something that both father and son could demonstrate

with wordless power.

It is left

to Corky the loyal dog to mourn his friend and for June’s reporter beau to display a

rare conscience by burning his notes to save future electro-exploitation of

humanity.

George

Waggner continued in the genre with two more releases in 1941 that we will

examine: the castle treasure-hunt Horror

Island and then more impressively guiding Lon Chaney Jr to true screen

immortality as The Wolf Man.