DRACULA:

FROM STAGE TO SCREEN

Bram Stoker

never lived long enough to see his most famous creation Count Dracula

dramatized on stage or screen before his death in 1912. The book achieved a

celebrated literary and cinematic afterlife, recreated countless times by each

future generation on film. He had made an abortive attempt to stage a play version

whilst he was still business manager for Sir Henry Irving at London’s Lyceum

theatre; Stoker had not only partly based Dracula’s distinguished appearance on

Irving himself but hoped his employer would play the title role. However, after

hearing a staged reading of it, Irving reputedly pronounced it ‘Dreadful!’

Over the

next few years there were to be two films that unofficially introduced the

world to the Count. F.W. Murnau’s aforementioned plagiaristic masterpiece Nosferatu in 1922 is the most famous

(albeit poorly disguising its obvious source). The year before, a little-known

Hungarian film appeared called Dracula’s

Death which borrowed the title character and not the plot from Stoker. It

concerns a music teacher within an asylum who only believes himself to be

‘Drakula’ (carefully using the more distancing Hungarian spelling), so only has

a passing connection with the novel.

In 1924

actor-manager Hamilton Deane decided the time was right to make an (as it were)

full-blooded bid to officially present Dracula

for the theatre as part of his touring repertoire. In Universal’s valuable

documentary The Road to Dracula by

David Skal, company actor Ivan Butler recalled that “He had to cut it down, for expense for one thing…It was a sort of

skeleton of the original”. Deane’s production was largely responsible for

the look of the Count that we know so well today. Rather than the aged,

moustached, longer-haired novel’s description, the stage Dracula was a middle-aged,

debonair figure only ever seen in evening dress and reminiscent of a gentleman

magician – an atmosphere augmented by the stage production’s elaborate magic

effects including a false-bottomed coffin for him.

The part was

played on tour by a number of actors, most notably Raymond Huntley who still

holds the record for the literally thousands of times he played the role across

England and America. The play was a smash hit, so inevitably Broadway came

calling. To transfer to the ‘Great White Way’ however, producer Horace

Liveright wanted changes, for example to render the anglicisms suitable to a

New York audience. He brought in playwright John L Balderson to streamline the

script.

At that

time, 1920s American audiences had no real knowledge of vampires. The closest

approximation they had was the alluring sexuality of Theda Bara, heating up the

screen as the exotic ‘vamp’ archetype in films like The She-Devil. Liveright felt that his Dracula actor should have

some of her ‘foreign’ mystique and marketable sex-appeal. His problem was who

to hire, on a limited budget almost all of which was already spent on the

supporting cast. He couldn’t afford the usual box-office boost provided by a

star name. His prayers were about to be answered from an unlikely quarter…

ENTER LUGOSI

Bela Lugosi

(Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó) was born in Hungary in 1882. After an early film

acting career in supporting roles, his union organiser activities during the

unsuccessful communist revolution of 1919 forced him to flee his native

country. Initially he tried his hand in German Weimar cinema (which may explain

the intense, somewhat Expressionist style of his movie acting) before he pitched

up in America’s New Orleans looking for theatre work. Having no command of

English, Lugosi had to learn his early parts phonetically. When the Broadway

producers heard about him, they realised that the otherwise limiting attributes

of this ex-pat actor could actually be perfect for them; they even allowed for

his still-hesitant grasp of English by agreeing to direct him in French. His

strong Hungarian accent (local enough to Dracula’s home region) coupled with an

air of commanding, aloof mystery satisfied the needs of the role – moreover

they were under time and financial pressure to complete the casting.

Debuting in

October 1927, the Broadway production was a great success, and although in

retrospect it simultaneously made Lugosi and imprisoned him for ever in the

role’s association, many actors would gladly have bargained for the

opportunity. In his late 40s suddenly Lugosi was a Broadway star, unnerving

male and female audiences alike in what the posters trumpeted as: ‘New York’s

latest shudder!!’ He ultimately went on to play the role thousands of times, 33

weeks in the Broadway run and then on one of two simultaneous tours, the other

Count played by Raymond Huntley. Universal Studios caught the hit show early in

the run, having already established a practise of scouting for theatre talent and

plays to fulfil the new demand for talking pictures and ‘well-spoken’ actors to

showcase in them.

DRACULA (1931).

“In all the annals of living

horror…One name stands out as the epitome of evil!”

Ever since

Carl Laemmle had founded Universal Studios back in 1915, he had wanted to

produce a film of Dracula – yet even though the studio had earned huge success

with The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of The Opera, both starring

Lon Chaney, he was apprehensive about its viability. Until that time, horror

had not become an established genre like westerns or romance dramas. Finally it

took the enthusiasm of his son Carl Laemmle Jr to finally commit the studio to

making it and $40,000 secured them the movie rights to the play.

Initially,

the studio aimed to minimise its risk as much as possible by persuading the

proven film star Chaney to take the lead part instead of transplanting the original

Broadway cast. Negotiations got as far as offering Chaney a three-picture deal

and the enticement of a talking sequel to The

Phantom of The Opera. Tragically, audiences would be denied his startling

craft in both roles when cancer took his life in 1930. One connection to Chaney

that would remain was the hiring of his long-time collaborator Tod Browning as

director.

Whilst we

can only speculate as to how Chaney would have no doubt metamorphosised himself

to fit Dracula’s physicality, Lugosi imprinted his own attributes onto the part.

Aside from the air of exotic mystery and intensity in his playing, the unusual

rhythm and word emphases of his non-native English delivery of the lines is

still the most widely-imitated version of Dracula – in much the same way that

Olivier’s distinctive speaking of Richard

III is inextricably bound with that role. Sadly, this would prove part of

the fateful draw-back for Lugosi, as unlike Chaney’s trademark as ‘the Man of a

Thousand Faces’ he was using his real accent that could not be adapted to other

roles for greater versatility.

Lugosi had

to campaign hard to be cast in the film, denigrating himself so far as to

contact Bram Stoker’s widow for extra support. Before settling on him, Universal

had considered such names as Conrad Veidt and Paul Muni. Finally, the studio

agreed on Lugosi. A further humiliation was his agreeing to a fee of just $500

a week for the seven-week shoot (a quarter of that paid to David Manners for

playing the supporting role of Harker). Presumably he tolerated this exploitation

because he knew instinctively that this was the chance of a lifetime for an

actor to make his name. Allegedly during the shoot he maintained an aloof air

from the rest of the cast, preferring to walk about seemingly hypnotising

himself by repeatedly intoning “I am

Dracula”. Perhaps this speaks as much about understandable insecurity and

the pressure upon him as any perceived arrogance of manner.

The overall

budget for the film was set at $341,000, less than was originally intended for

a proposed full re-imagining of the novel; the aftermath of the catastrophic

stock market crash of 1929 left the company no choice but to tailor the film

closer to the less ambitious play.

The prologue

sequence transporting us to olde-worlde Transylvania begins with an impressive

glass shot that augments the real shot of the carriage on a road at the bottom

with the winding path up to the ghoul’s fairy-tale Castle Dracula. Inside the

carriage, the first dialogue ever spoken in a pure horror film is by the young

Carla Laemmle as an American tourist en route. The famous orchestral music

refrain we hear is from Swan Lake and

would recur in other Universal horror films such as The Mummy and Murders In the

Rue Morgue.

In filling

out the rest of the cast, Asie from Herbert Bunston as Dr Seward, Edmund Van Sloan was the only other Broadway cast

member brought in to repeat his crew-cut boffin of a Professor Van Helsing, a

vivid presence if lacking the attractive, dynamic energy and gallows humour of

the novel’s character. Charles Gerrard, the cockney sanitarium orderly, (“They’re all crazy!”), was recruited from

James Whale’s film of his distinguished stage run of Journey’s End. Whale would pick up the horror baton from Browning

to direct Frankenstein for Universal

the same year.

For my

money, the best performance among the fresh talent drafted in is the elsewhere

Broadway veteran Dwight Frye as Renfield, a wide-eyed manic bundle of schizoid energy

with a memorable snickering laugh who becomes Dracula’s spellbound servant. (This

began his typecasting into subservient character parts such as Fritz, the later 'Ygor' archetype, in Whale’s Frankenstein). One of the major changes

in translating the book to the stage (and film) version is that it is he and

not his employee Harker who initially goes to Castle Dracula to secure the deal

for the vampire’s new home at Carfax Abbey in England. It neatly strengthens

his relationship with Dracula - and mercifully gives us less of David Manners

whose scenes with Helen Chandler’s Mina are slow, bland drawing-room melodrama

which deaden the pace in the second half.

To be fair

to the juvenile leads, the play and film translation had to sacrifice much of the

location scenes and characters that work (in an uneven book) in favour of their

relative modest budgets. It’s easier to stage talky expository scenes in a

single English location than showing the book’s climax moving to Transylvania

for example – but it does mean that the one forgets that it’s supposed to be a

horror film about a terrifying supernatural threat not a modern love story of

romantic trials, particularly after the halfway point. The aping of current

theatre styles is compounded by updating the period to the 1920s for budgetary

reasons.These interpretations of Stoker also both omit most of the trio of

heroes committing excitingly to kill Dracula under Van Helsing’s leadership. In

the novel, Quincy Morris, Arthur Holmwood (Lucy’s fiancé) and Dr Seward are

former suitors of Lucy who make a tribute pact as she is dying to end the

vampire with Van Helsing and Harker – thus implying how powerful an adversary

just this single undead figure of evil must be. Now, however, Dr Seward is

Mina’s father so it is a less dramatic father and mentor dynamic in opposition.

The less

successful special effects in Browning’s film involved the same bats-on-wires

as the stage production - which transform into Dracula off-screen - and a storm

at sea sequence taken from Universal’s 1925 silent film The Storm Breaker which is speeded-up, owing to the slower camera

speed of silent footage. There are significant improvements that the film makes

of course. John Ivan Hoffman’s superb set designs give us the huge decrepit interiors

of Castle Dracula complete with a sweeping staircase, plentiful cobwebs and

spiders that only nowadays could be lavished on a Broadway production. (It even

has an insert shot of inexplicable armadillos wandering about). This was

achieved like the opening vista of Transylvania by a glass shot placed over the

lens, adding the extra expanse of scenery ‘live’ during filming.

My favourite

of the invented plot changes is the opportunity for Dracula and Van Helsing to

meet face to face in a dialogue scene as worthy enemies verbally challenging

each other. One of the weaknesses of the novel is that we don’t get this

satisfaction. After over-long research preparations for pursuing Dracula back

to Transylvania, the team hurtle across Europe, suddenly rip open the Count’s

coffin on sight and while Quincy slits the vampire’s throat, Arthur stakes him

to death. There is no time for Dracula to awake and for us to savour any kind

of confrontation. In fact, other than the deliciously suspenseful early scenes

of the vampire with Harker in Castle Dracula, the Count is virtually absent

from the rest of the book till the end. In the film he has a more fitting

amount of screen time, and visits Van Helsing who ignores Dracula’s boast of

command over Mina and his demand that he return to his homeland. The

Professor’s will equally proves too strong for the vampire’s hypnotism.

Finally, we also gain the extra pleasure of seeing the expert older hero

himself executing the vampire, albeit staged less than triumphantly. (Dracula’s

long death groans were cut from the soundtrack until the 1990s Laserdisc

release put then back).

Though Tod

Browning could identify with the ‘alien misfit outsider’ status of Dracula, a

theme he mined powerfully in films like the later Freaks (1932), he struggled with adapting his style of shooting

silent films to the new sound medium. As far as he could, he cunningly filmed

scenes without dialogue which did add to the eerie atmosphere, such as when

Dracula is hypnotising his victims wordlessly. According to the actors, he was

not a strong guiding hand on set, deferring frequently to his superb

cinematographer Karl ‘Metropolis’ Freund

for many of the stylistic filming decisions. Freund was full of creative ideas

and with such striking techniques as tracking shots leading us into the castle

and the sanitarium, as well as great use of lighting and fog it’s no surprise

that he went on to supplement his camerawork by fully directing Universal

horror classics like The Mummy and Mad Love.

At the very

end of the film, the first cut included an epilogue taken from the New York

theatre run in which Van Helsing speaks directly to the audience, playfully

assuring them not to blithely dismiss what they have just seen as pure fantasy

because: “…after all, there are such

things as vampires! This coda was later dropped.

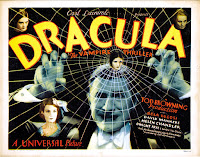

To bolster

its chances on release, the studio gave Dracula

a splendidly eye-catching poster campaign in various full-colour designs,

possibly the most memorable featuring a spider’s web with Lugosi poised at the

epicentre, surrounded by his female prey from the cast caught in his terrifying

snare. Nowadays these poster fetch huge sums as valued collectors’ items.

When Bram

Stoker conceived Count Dracula, he had consciously or not played on Victorian

cultural paranoia in different forms. There was an irrational xenophobia about foreigners,

racism toward anyone who was not a product of polite English society. In awakening

both Lucy and Mina’s deep sexual yearnings and desire to fulfil them, the book

also aroused traditional men’s fears of female emancipation, their dominance

also threatened by the Suffragettes. Dracula’s character could even be viewed

as a metaphor for the terror of contracting sexually-transmitted diseases, a

living virus infecting us as a result of consorting with the unclean outsider. (Stoker

allegedly suffered from tertiary syphilis). These anxieties still resonated in

1920s western audiences, particularly in the post-war mistrust of other

countries. This may help explain the peculiarly unnerving effect that Lugosi’s

portrayal had on both men and women in cinemas.

No comments:

Post a Comment