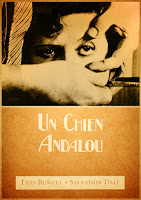

In 1928

Spanish director Luis Bunuel launched his challenging career as a film-maker

with the infamous Surrealist short Un

Chien Andalou. It was full of the themes that had obsessed Bunuel since

childhood – and by collaborating with artist Salvador Dali ensured that its bizarre

symbolic imagery deliberately made no concession to commonplace narrative

logic.

Luis Bunuel

was the eldest son of seven, born into a wealthy family in the small Aragon

town of Calanda in Spain. His father Leonardo had inherited a fortune and rather

than being a role model of the hard work ethic spent his days as a gentleman of

leisure. Luis was similarly indulged by his mother who regarded her oldest boy

as a saint, displaying a portrait of him on a makeshift altar of paintings of

popes.

Bunuel’s

character was hugely influenced by his environment - a closed, isolated

community with a rigid hierarchy and strong Catholic faith maintaining a status

quo of respect between peasant and landowner. Religion permeated all aspects of

Bunuel’s life and he developed an ambivalent relationship with it and all forms

of authority throughout his life. He went to a Jesuit college, a branch of the

faith notorious for its strictness of discipline. There, the Brothers’

merciless views on abstinence crystallised in him an inextricable link between

the forbidden ‘voluptuous’ pleasure of sex mixed with death.

Anthony

Wall’s excellent BBC Arena

documentary The Life and Times of Don

Luis Bunuel (1984) features extracts from his autobiography read by Paul

Scofield and revealing archive interview films. When asked what made him choose

film as his medium of expression, he replied “Sheer bad luck” because he considered himself a lousy painter and

writer. The weapon of choice Bunuel felt comfortable with was the filmed visual

image. Somewhat tongue-in-cheek, he added: “Acting

is a profession for layabouts. I’d have liked that…A nuisance but it’s

well-paid”.

Bunuel

studied insect science at the University of Madrid, which became a life-long

fascination and shows up within the imagery of his films. His student years were

a pivotal point of inspiration in his life, introducing him to his long-time

friend and creative partner Salvador Dali from whom he became inseparable. He

also became heavily immersed in the Surrealist movement, via such luminaries as

Man Ray, amongst whom he would fraternise at La Coupole and other celebrated venues

for the artistic café society set. Although the Surrealists were at face value a

group of radical café intellectuals, they were not simply poseurs or aiming for

artistic posterity in their work. They wanted to change the society around

them, which they despised for its colonial imperialism and oppressive religious

tyranny. Even though Bunuel was only involved with them for roughly three years,

their mission statement added energy and purpose to his own expression.

After

university Bunuel went to Paris to pursue the literature and arts scene. By

now, cinema possessed him as a future career. His mother had already been

horrified by this decision. Like many (including some professional actors as we

have seen), she regarded movies snobbishly as something for the common-folk. In

Paris, he drenched himself in the latest films – watching three a day. He loved

the Hollywood comedy shorts of such performers as Buster Keaton and Harold

Lloyd, but it was the work of director Fritz Lang that had the most profound

effect upon him, in particular Destiny (see

my review of 3/1/2016). Whilst in the city, he became apprenticed to

influential French director and critic Jean Epstein which taught him much about

form and technology as assistant to his cameraman.

Jean-Claude

Carriere, later co-writer on many of Bunuel’s films, recalled in the Arena documentary that the director had

always greatly respected the power of imagination. Bunuel made a point of

training himself to allow uninterrupted daily time for flights of fancy and

would obey wherever they took him creatively. This free-associative philosophy is

very clear even in his first film. In fact, Un

Chien Andalou came about through the most unstructured of free-form

imagination - dreams recounted by himself and Dali in conversation one day.

Bunuel dreamt of a knife cutting an eye. Dali imagined his hand crawling with

ants. Such images became famous “irrational

elements” in the final movie. Bunuel and Dali concocted a script together

in seven days, which is easier to believe when you consider the ethos that

guided their writing: “Refuse any image

that could have a rational meaning”. Theirs was a truly democratic

collaboration. Any image that impressed them for whatever reason was in. If

neither liked a particular idea, out it went.

Un Chien Andalou was shot in Paris - financed,

despite her earlier protestations, with money from Bunuel’s mother, the

cinematography provided by Albert Duverger and Jimmy Berliet. The film is an

oddly upbeat, bracing ride despite being heavy with dark symbolism. This is in

part because ever since its premiere at La Coupole, it has always been

presented matched to a soundtrack of spirited Argentine tangos and the opera Tristan Und Isolde (played on phonograph

records behind the screen when first shown). The opening is a brutal, literal

eye-opener as a man (played by Bunuel) sharpens a straight razor, gazes up at

thin clouds crossing the moon and imitates this by slicing open the eyeball of

a young woman (Simone Mareul). If it’s any remote consolation, the hairy face used

for the victim is actually a donkey, (presumably already expired, bless him).

From here, the chain of events is tenuously linked in much

the same way as dream logic jumps – the title cards alone indicate this in

going at one point from ‘Il était un fois’

(once upon a time) to suddenly ‘sixteen

years ago’ with no responsibility to show the effect of time’s passage.

A young man (Pierre Batcheff) dressed in a nun’s habit and wimple with an

ornate box around his neck cycles down a street and collapses, to the horror of

the young woman from scene one. He appears dead. She lays out his garments and

props on the bed in a ritual design. He re-appears at the door, his hand

crawling with ants, recalling Dali’s dream and Bunuel’s fascination with

insectoid life in an insert effect shot skilfully achieved. A young woman on

the street below pokes at a severed hand with a stick, drawing a crowd till a

Gendarme arrives and puts it into her box, striped like that of the young man now,

in the apartment above. Somehow this, culminating in her being run over, turns

him on as he watches events from the window, inflaming his desire to grasp at

his partner’s breasts and buttocks while a close-up of his face portrays an

upward expression of yearning reminiscent of Christ on the Cross (appealing to

God)?. It’s far too tempting a proposition to analyse the meaning of some of

the imagery on offer rather than letting it wash over one like hallucinogenic

waves. His perverse passion next manifests itself in an image that neatly

combines the director’s interwoven feelings about sex and religious oppression,

as the man tries to drag himself across the room toward her whilst being

harnessed to two grand pianos topped with dead donkeys, one of them bleeding gorily

from one eye (having donated it in the first scene?) with a pair of bemused

priests pulled behind for good measure.

The young man’s hand is trapped through a door, teeming with

more ants - naturally. The door-bell rings, cutting amusingly to disembodied hands shaking

a cocktail shaker – possibly symbolising merry opportunity - your guess is as

good as mine. This introduces us to a slightly shady man in a Fedora (Batcheff

again) who divests the protagonist of his ‘costume’ gear and throws them out of

the window. He forces the hero to stand in the corner like a naughty schoolboy

in class, the comparison all the more inviting as he is made to hold out text

books in each hand. I suspect here Bunuel was raging against the cruelty of his

Jesuit teachers as the hero’s props turn into pistols and he shoots the

bullying doppelganger. His double then materialises in a forest clearing,

attended to and then carried away by local men.

Marueil, back in her apartment, witnesses a death’s-head moth

on a wall, a close-up hammering home its significance. We then return to normal

obscure service by Batcheff in the room with her, wiping his mouth away to

replace it nightmarishly with her armpit (a part of the anatomy repeatedly referenced

in the film). She then appears on a beach with a third young man, with whom she

discovers the washed-up remnants of Batcheff’s nun outfit and striped trinket

box on the shore. The couple walk away, canoodling - but a happy ending is

thwarted by the stark final image, ‘Au Printemps’

(In Spring), showing them buried to their upper torsos in the sand like

disturbing shop mannequins.

At a pacey two-reels (21 minutes) Un Chien Andalou is a madcap and enjoyably daffy roller-coaster of

Freudian cheese-dreams and a great concentrated example of Surrealism, early

Bunuel and Dali (transplanted into film as the artist would later do with dream

visions for Hitchcock in Spellbound).

Dali wasn’t the only one of the twosome to go to Hollywood. The American movie

capital thrilled Bunuel as a life-long fan of their works and he jumped at the

chance of a highly unusual six-month contract offered by M-G-M that allowed him

to study the departments of editing, writing and ‘studios’. His sabbatical sadly

did not translate into immediate directing contracts, yet later on yielded his Hollywood

projects Robinson Crusoe the first American

film released in Eastmancolor in 1954 and The

Young One (1960).

Bunuel’s place in movie history was to be assured though with such European classics as

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) and That Obscure Object of Desire in 1977.

No comments:

Post a Comment