“Look at me and see what seventeen

years in the grave has done to me…”

The downward

slide of Tod Browning’s directing career had begun with his most recent film,

the disappointing Mark of the Vampire,

and increasingly he found it hard to get projects off the ground at M-G-M. He wanted

to make a voodoo tale called The Witch of

Timbuctoo at the end of 1935 but this was blocked at script stage due to

pressure from the British censors. In The

Monster Show, Browning aficionado David J. Skal records: “Great Britain had

requested the removal of all black characters for fear that the witchcraft

scenes would ‘stir up trouble’ among blacks under British colonial rule” - a level

of appalling fear-mongering racism that also weirdly echoes the plot reasoning

we have just seen for the extinction of the occult knowledge by the authorities

within Revolt of the Zombies.

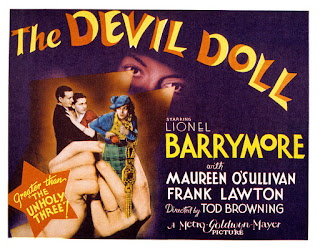

Browning was

however able to reshape his story into The

Devil Doll (1936) which combined his oft-used theme of revenge with

voodoo-esque hocus-pocus in modern-day France. It was loosely based on Abraham

Merritt’s 1932 novel Burn Witch, Burn,

one of the writer’s works steeped in his fascination for witchcraft and the

occult. Browning enlisted experienced genre screenwriters Garrett Fort, Guy

Endore and credited director-turned-actor Erich Von Stroheim to weave together

a film that not only moves kinetically but also its audience in an unusually

affecting ending for a hard-nosed vengeance picture.

The premise

is based around Lionel Barrymore (last seen in Browning’s Mark of the Vampire) as Paul Lavond, one of two escaped convicts

who has spent seventeen years boiling with the desire for revenge after being

framed as a murderer and robber of his own bank by his three partners. His

fellow escapee is mad scientist Marcel, desperate to get them safe haven back

with his wife with whom he has been experimenting on something unrevealed yet

potentially world-changing. He is played by Henry B. Walthall, who gained fame

as the Confederate General locking horns with the Ku Klux Klan in Griffith’s

controversial Birth of a Nation. The

two fugitives are taken in by Marcel’s equally eccentric wife Malita, embodied by

Rafaela Ottiano who specialised in memorably macabre roles. Possessed of fierce

eyes and a Nefertiti white hair streak recalling Elsa Lanchester’s Bride of Frankenstein, Malita is the

Lady Macbeth-like engine urging on Marcel’s crackpot technology.

The nutcase

couple take Lavond into their confidence, showing him their incredible results

in miniaturising living dogs to one-sixth normal size. (The effects in this

sequence rely on a fairly basic double-exposure, which only noticeably mars

itself in the evident outlines around the superimposed figures). They base their

rationale for such crazed ingenuity on the potential for reducing the global human

population and future resource shortages. The only downside is that shrinkage of the

living atoms also erases the subject’s memory – yet that opens up the possibility

for voodoo-style mental subjugation in the ‘right’ hands. Lavond’s horror at

seeing them progress to their “peasant halfwit” servant girl Lachna (Grace

Ford) is tempered by the macchiavellian Malita pointing out this usefulness of

Marcel’s technology in enabling a unique method of justice for Lavond if they

relocate to his home of Paris. She uses the sudden death of her husband mid-process

as emotional leverage to persuade Lavond.

Meanwhile in

gay Paree, Lavond’s trio of sinister ex-partners have now read in the paper

that their old friend is on the loose, so with feared retribution on the cards they

post a 100,000 franc reward themselves for his capture. The plot now heads into

the familiar horror territory of systematic revenge carried out on the multiple

guilty parties, rendered even more familiar by Browning recycling his leading

man disguising himself as a little old lady - Lon Chaney in 1927’s The Unholy Three (see my Chaney reviews 12/2015) - to undertake his

plans undisturbed under the frilly cloak of an elderly lady selling toys.

To be fair,

the drag impersonation allows Barrymore an added dimension of compassion and

vulnerability that prevents his grim, furrow-browed mission calcifying into a

one-note performance. This is emphasised in his scenes with his daughter Lorraine

(Maureen O’ Sullivan, who had been playing Tarzan’s Jane for M-G-M and went on

to a long and praiseworthy career as well as being mother to actress Mia

Farrow). He cannot bring himself to reveal his real identity when he visits her

at the launderette she has been reduced to slaving in. He must care for her at

a remove whilst in disguise, which only fuels his need for vengeance even more.

One by one,

the three banker scumbags are dispensed using the rough and bizarre justice of

Marcel’s scientific breakthrough - and some much more impressive special-effect

scale work. Arthur Hohl’s Radin is astounded by the old lady’s amazing, obedient

‘toy’ horse and visits her, whereupon he is paralysed into becoming a servile

mini-mannequin himself. Next up, Lavond’s old dame sells a Lachna ‘doll’ to the

wife of the second criminal, the bearded and rotund Couvet - Marx Brothers’

film veteran Robert Greig – and negotiates some convincingly- upscaled bedroom set

furniture to administer a bedside manner of poisoned-dagger paralysis to him

and steal his wife’s jewelled necklace.

If this is

beginning to sound like the story of Browning’s The Unholy Three, the blatant reworking goes further: a police

inspector comes to make routine theft enquiries connecting the old lady to the

robbery and the ensuing furtive hiding of the jewel plays as an almost

identical but less tense rehash of Chaney’s scene in the original movie.

By now, the

last evil member of the triumvirate has the benefit of a police protection detail

around him yet Lavond has threatened him in a encoded letter that unless he “Confess

and be saved”, he will still die at the stroke of ten. Even a roomful of cops

can’t save him from the remote-controlled Radin, hidden with macabre humour as

a Christmas tree bauble. As he is about to stabbed in the leg by the

mini-assassin, Radin owns up and Lavond is at last exonerated.

Usually in

horror films of the period, this is where the movie ends and often in a detrimentally

rushed climax. One of the plus points of the extra running time that takes The Devil Doll to 78 minutes is that

after Malita fails to convince Lavond to go on with the work, the purgative

laboratory blaze that follows permits a little more breathing space for character resolution and leads him to make restitution with his daughter.

Their last meeting is most sensitively handled by the actors and Browning.

Lavond, as himself, pretends to be a friend instead of revealing who he really

is to Lorraine. He expresses all his pent-up love, regret and future hopes for

her as if conveying them as a second-hand message – his final parting atonement.

He leaves her and her boyfriend, exiting with the self-sacrificing heroism of

Rick Blaine in Casablanca and giving The Devil Doll an unexpected and

touching ending.

No comments:

Post a Comment