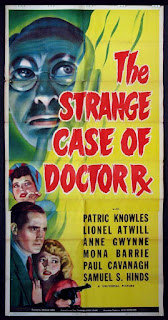

In April

1942, Universal presented the public with a curate’s egg in the cracked shape

of The Strange Case of Dr RX. It was

a sleuthy, light-hearted horror film whose comedy doesn’t always sit

comfortably, and saves any scant horror flavour till the last few minutes where

it is shoe-horned in as if from a different film. The most disappointing aspect

though is the fooling of the public using posters that promised another mad

scientist role from Lionel Atwill - the original Dr X in Warner Brothers’ 1932 feature. In that film, his part was a

red herring that distracted us from the real murderer but his was a lead role.

Here, he only sporadically pops in and out to unsubtly suggest his involvement

before the laughably rushed denouement. (This under-utilization of his talent

by the studio also occurred later in the year with The Night Monster (see review 13/3/2017).

Clarence

Upson Young wrote both screenplays and here introduces his signature style of

lazy and preposterous exposition, only squeaking by due to the facetious comedy

tone. It didn’t help that Dr Rx went

into production with an unfinished script, so the actors improvised much of

their dialogue to augment the non-sense on offer. Director William Nigh had

established he could steer a ship of awfulness with Boris Karloff in 1940’s The Ape and later with Bela Lugosi in Black Dragons (see 9/1/2017 and 1/3/2017

respectively).

The wastage

in Dr Rx isn’t just restricted to

Atwill – the cast on the whole are better than the material offered here,

something we can struggle to claim with Poverty Row efforts. Patric Knowles who

we last saw as the fiancé in The Wolf Man

(1941) is here given more elbow room as a light leading man, private eye Jerry

Church returning from a year in South America to a murder mystery. He’s clearly

good at his job as he can somehow afford the type of ritzy, well-appointed

apartment normally only seen in high society movies.

Even more

improbably, Church has his own valet, Horatio B. Fitz Washington. On the plus

side, he is played by Manton Moreland, the black actor who would single-handedly

enliven King of the Zombies (1941)

the following month. The bad news is that despite the grand character name, he’s

required to demean himself to being a saucer-eyed, dim-witted submissive. This

is an enduring shame as his comic timing is excellent. Here, what passes for an

added dimension is that he has a terrible memory which he tries to compensate

for by a system of linked images that merely side-track him. When he gets a

message to pick Church up from the airport, he processes it as “Church –

airport – airplanes – clouds – birds – nest –eggs – breakfast”. On being woken

up by his long-suffering boss having to make his own way home, he apologises:

“I was slightly negligee”.

The other

exponent of comic chops who labours in the salt mines here is former Stooge

Shemp Howard, he of the lovable pugilist mug who resembled his brother Moe so

closely. He is the cop sidekick to the rakishly-moustached Det. Capt. Bill Hurd

(Edmund MacDonald, an uncredited anarchic miner in 1940’s The Invisible Man Returns). As Church’s old partner on the force, Hurd

is desperate for Church to postpone his planned Boston retirement and solve the

case of Dr Rx, a vigilante murderer who has so far killed five hardened

criminals that were acquitted by the justice system. The case-readjuster leaves a card teasing the

police with his surname and the victim number.

Judge

Crispin also implores Church to help him. He fears being on the list as the

presiding judge forced to let three of these reprobates go free. Crispin is

another in Harvard alumni Samuel S. Hinds’s gallery of erudite portrayals of

gravity following his kindly Dr Lawrence in Man

Made Monster (1941), He would dispense the law again in Son of Dracula (1943) before achieving

screen immortality as Pa Bailey in 1946’s It’s

a Wonderful Life. His offer of $10,000 initially makes no difference to

Church (well it wouldn’t considering the Art Deco splendour in which he lives).

For love

interest there is Kit (the stunning Anne Gwynne) who appears to be Church’s

girlfriend for a large chunk of the film and then is revealed to have been married

to him while abroad. This is one of the many shoddy story details that Young blithely

drives past us on his way over the cliff of quality. Her horror roles took in The Black Cat (1940) and Black Friday (1940) and later 1944’s House of Frankenstein. She does her own

investigation into the case that increasingly embroils her husband, and wishes

she hadn’t when she sees the white-haired catatonic that fear of Dr Rx has made

of a previous private dick.

It seems

that no-one is safe from the tendrils of Dr Rx. Even in the court-room he still

causes the death of his next target, gangster Tony Zarini (Matty Fain) just

after he is acquitted. He is not allowed to enjoy his freedom; just after

taking a medicinal powder, he keels over dead from apparent poisoning. Atwill,

wearing inscrutable coke-bottle glasses, looks on impassively. He may as well shroud

his face with a cloak and chuckle “Mwaw hah ha ha” for all the attempted

ambiguity on display.

What

qualifies as a strange case indeed is the sudden temporary shift in tone in the

last ten minutes. Church and Horatio are forced at gunpoint to drive the Elephant

Man- hooded, sinisterly rasping Dr Rx to a secret location. After evading their

cop pals in a car chase, the plot makes a sharp left turn toward serious horror

whereby Church is strapped to a gurney in a laboratory and told introduced to

the Dr’s gorilla who is imprisoned behind bars: “He is very stupid but he will

be very smart…and you will be…not so smart” ad-libs the Doctor badly with Atwill’s

voice. There is a stark image of genuine unpleasantness to end the scene in how

the Dr. forces Horatio’s eyelids to remain open as he watches the impending operational

terror, albeit involving a man in a monkey suit. The inhabitant of said suit was Ray ‘Crash’

Corrigan, the enterprising athlete who went from fitness trainer to the stars

to science-fiction roles, most famously as It!

The Terror from Beyond Space (1958), helped by being the owner of his own

gorilla costume.

Just as

perplexingly we are then thrust back into the relative safety of the real world

where we learn that poor Church was found wandering down by the waterfront and

is now a white-haired hospital convalescent. The police bring in Atwill, now

named Dr Fish, to give his medical opinion. As he takes out his notebook,

surely now he will incriminate himself by making witnessed notes in the same

handwriting as the killer? But no, it was all a ruse to unmask the real

murderer – Judge Crispin! By comparison with this denouement, Scooby Doo’s revelations seem sophisticated

as the unfortunate Atwill, in on the plan, has to administer us the foul-tasting

medicine pill of Crispin’s motivation. He was an egomaniac who wanted to

mesmerise the jury with the brilliance of securing each gangsters’ freedom just

so he could then single-handedly bump them off. There is a laughable irony in a

man having persuasive brilliance in a court-room yet leaving none to explain

his own loopy logic. As for what happened to Church in Crispin’s basement

dungeon, he is at a loss: “Suddenly the lights went out”. We share his

confusion – not helped by the bizarre epilogue of Horatio answering the door to

the happy couple with his own white hair and insane giggle for no reason.

Sadly for

Lionel Atwill, he could not escape the ruinous odour of a real-life court case

he was implicated in. Soon after the release of the film, on July 1st ,

he was indicted for perjury in the unsavoury Sylvia Hamalaine scandal (see my

Lionel Atwill article), and from here onwards he would be ill-served by a

hypocritical industry who would exploit some measure from his name value while

he spiralled downward to an untimely death.

No comments:

Post a Comment