‘You may have lived or perhaps

dreamed the story you are about to see. To many of you it may be

This

fanciful prologue, like Columbia’s other B-movie horror Cry of the Werewolf released on the same day, prepares us

ambiguously for what may or may not be believable over the next sixty-one

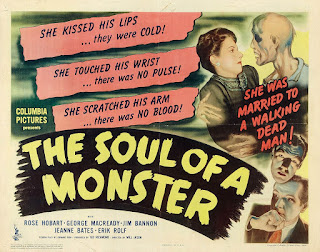

minutes – in more ways than one. The Soul

of a Monster (1944) has worthy elements in it that with more time and money

could have developed into something substantial. Instead, it’s a fitfully

appealing film whose deep musings struggle to emerge through the confines of a

clunky script and hampering by some weak B-movie cast members.

The director

was Will Jason in what appears to be his first feature after a lengthy roster

of credited shorts. The screenplay was by a writer already familiar with the

genre, Edward Dein, who amongst his credits had previously provided additional

dialogue for Lewton and Tourneur’s The

Leopard Man (1943). This was intriguing to discover as the tone of The Soul of a Monster reminded me of

their work before finding this out. It aims for higher-minded goals than the usual

programmer fare, being a meditation on religious faith and the perils of

bargaining with the Devil - or to quote

the Bible’s Matthew (8:36): ‘For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain

the whole world, and lose his own soul?’

If producer

Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur could have guided the material to

their demanding and tasteful quality level, it could have overcome its

limitations to become a stylishly shot and artfully written piece. Unfortunately

neither Jason nor Dein are able to rise to the occasion so we must be content

with hints along the way of what might have been. The story concerns famously

altruistic surgeon Dr George Winson (George Macready), who lays prematurely dying

while his devoted wife Ann (Jeanne Bates) loses her faith in bitter helplessness

at a God she perceives as turning His back on such an undeserving man. Such is

the potency of her love and recrimination that she stares into the fireplace’s

flames and desperately invokes “If there is another power – whoever you are,

wherever you are – I beg of you, save him’.

Before you

can say Law of Unintended Consequences, we are treated to a bravura attempt at

a strong visual set-piece that introduces our designated nemesis. A retired

couple run over an unidentified woman and are mystified that she vanishes from

sight. A sparking power cables dangles alarmingly down upon the street as the

same enigmatic lady strides obliviously past. Two council workmen find their

torches flaring all of a sudden as she passes them. Fans of Brian de Palma’s The Fury (1978) may get a pleasant

little jolt of recognition from this sequence’s staging of the wake created by

a supernaturally-boosted character. She arrives at the Winson home and, without

so much as a proper introduction, more or less barges in and presents herself

as the implied demonic representative summoned by Ann – a brusque,

black-dressed, Joan Crawford-esque brunette named Lilyan (Rose Hobart).

From this

point, the film settles into a fairly humdrum battle of wills. In the evil

corner is Lilyan and

her devilishly-charged servant George (albeit on a

low-performance energy trickle for the most part) revived into such

unrecognisable primitivism that he kills his faithful pooch. On the side of

Good we have the sympathetic, wrong-headed Ann and the couple’s friend Fred

Stevens, an interesting character player named Erik Rolf. On the strength of his work here,

Norwegian-parented Rolf was sadly under-parted as mainly Germans in forgettable

war movies during his short life of forty-five years (though according to IMDB

his versatility in New York radio drama set a staggering record of over forty

separate roles in one week). Rolf gives Fred an intriguingly soulful, almost

furtive depth as a hero – to the point where I would have preferred him to have

swapped parts with Macready who plays George with a more routine competence

than his later distinguished turns for Kubrick in Paths of Glory (1957) and Blake Edwards in 1965’s The Great Race.

Wielding a

knife, George pursues Fred down a dark street one night in a scene that would

have been rendered a tense and memorable signature sequence under Lewton and

Tourneur. However, here it extends too long and is robbed of any tension. The

sole interest value comes from the frightened beat cop Fred literally bumps

into (bit-part workhorse of five-hundred plus movies Harry Strang) who launches

into an unlikely, biblically-slanted rant about the temptation to crime caused

by dark nights: “This ain’t blasphemy, but -“. His is one of many not always

subtle bids to drip-feed religious references into the script. As George looms

over Fred, our hero saves his own life, unwittingly warding off his would-be

killer by holding up his dropped crucifix, a fumbled resolution to an overly

protracted suspense scene.

The

depiction of the two antagonists is even more confused when George later agrees

to meet Fred in a restaurant. Somehow his homicidal stalking impulse seems to

have calmed enough to be in the mood for a civilised theological debate with

his old pal. Fred tries a subtle appeal to his conscience by framing George’s

awful condition as though it were a story conundrum plaguing Fred: “A body

without a soul would be a permanent torture. So hideous…so terrifying”, he

muses. George is having none of it and storms off, leaving his loyal friend to

defend his behaviour to the waiter, another purveyor of unsubtle Bible shoe-horning:

“Friend? Cain and Abel were brothers!” (For an urban neighbourhood, the local

church must have a pretty impressive outreach program).

It isn’t

only Fred who labours in vain to make himself understood; the dialogue

hamstrings everyone with vagaries. Poor meddling Ann cannot work out what the

devil is going on: “I don’t know what it is I’m fighting. What is this thing

that’s come into our lives?” she confides in Fred. He at least symbolises the simple emollient of trusting in faith rather than the Old Testament wrath on

offer around him.

Meanwhile

George has become a medical ambulance-chaser, almost salivating at what the

siren sound brings to his operating table. “That sound…It’s stimulating”. Dr

Vance not only realises his surgical colleague is running on a lean mixture, he

also presents unearthly physical symptoms of having no pulse and no reaction to

being stabbed with scissors. As Vance ex-stuntman Jim Bannon is wooden enough

to suggest he’s overdosed on anaesthetic, which coincidentally is how George

dispatches him for his suspicions.

Soon, Dr

Death’s malpractise catches up with him and the threat of post-trial

electrocution shocks George into a return to conscience. Once again though,

Dein cannot resist bludgeoning us with a word from his sponsors in an exchange

with Fred containing a specific Christ analogy:

“It isn’t

fair that Ann should carry my cross”

“You placed

it on her shoulder, George. Only you can remove it”.

Fred now has

both bases covered by already urging Ann to pray for him as well. Thus, even

the little Devil herself is no match for a born-again George, so full of holy

inspiration that he fatally advances on her, impervious to point-blank

gunshots.

The epilogue,

returning to George’s deathbed, does have a measure of poignancy to it. Pippa

the dog and Dr Vance back at his bedside confirm the prologue hint that it was

all but a dream. With a tear, George checks out but not before a lofty admonition

for us to walk the path of righteousness: “We wrestle not against flesh and

blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of

darkness in the world…” - to be fair, a refreshing change from a sweaty detective

leaning over an expired monster and saying “He’s dead”.

Whilst the power

of religion theme is heavy-handed, The

Soul of a Monster deserves credit for at least attempting nobler content

than a routine horror B-movie, albeit without the resources to best support the

intent.

No comments:

Post a Comment